rob-curran-sUXXO3xPBYo-unsplash

As I read the news, I get depressed by our continuing failure to slow the planet’s plunge toward environmental catastrophe. Targets for atmospheric CO2 levels are breached, plastic inundates the oceans while coral reefs disappear, wildfires rage in both tropical and boreal forests, while rare species are poached toward extinction. How to stop or at least slow this rolling disaster? Some seek solutions in technology — more solar panels, more wind turbines, pumping CO2 underground. Others promote personal efforts — turn down the thermostat, ride an e-bike, eat plants instead of meat. These are all worthy approaches. However, most environmentalists seem blind to the most impactful means for blunting multiple forms of damage to our planet, namely the reduction of the global population.

The argument for ignoring the impact of population is that it changes too slowly to affect the rapid processes of environmental degradation now in play. The notion is that we need to focus on approaches that will be effective between now and 2050 or it will be too late, and that irreversible ‘population momentum’ precludes timely effects of population change. These ideas are manifested in many blogs and magazines that deal with environmental issues and also in the major media.

However, contrary to these ideas, fertility rates, population trajectories and migration patterns actually can change, sometimes with surprising rapidity. This population malleability potentially has major consequences for a variety of environmental parameters including global warming. To understand this fully we need to look more carefully at the population projections provided by the United Nations and other organizations over the years, how they have varied and what the environmental consequences of that variation might be.

Uncertainty and Variation in Population Estimates

The population projections provided by the UN and other agencies are often treated as rock-solid certainties. They are not. In fact, there is substantial variation over time as well as between agencies. Thus, in 2002 the United Nations Population Division projected a 2050 global population of about 8.9 billion, while in 2022 the same organization projected a population of about 9.7 billion, a rather substantial difference. Further, estimates may vary widely between organizations with expertise in population analysis. For example, there are widely divergent estimates of population growth in sub-Saharan Africa with the UN projecting 2.1 billion in 2050 and 3.8 billion in 2100, while the the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis projects 1.9 billion and 2.6 billion for the same periods.

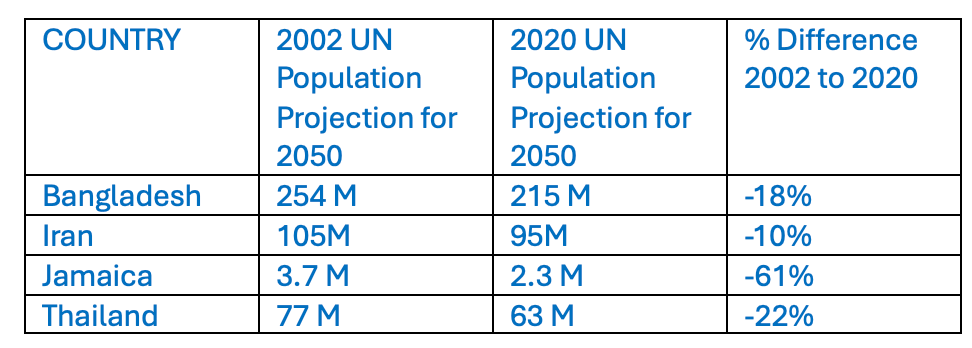

During the late twentieth century several nations with very different economic, political and cultural characteristics each underwent a ‘demographic transition’ that resulted in drastically lower birth rates. Thus, population momentum for these nations exhibited a rapid and profound change. Early UN population predictions for these countries for 2025 well exceeded actual current populations, while the early projections for 2050 substantially overshot more current projections. Some examples from these sources are shown in Table 1.

This data demonstrates that major reductions in birth rate and in total population can take place in less than the span of a single generation. These dramatic changes did not just happen by chance, but rather were usually the result of effective but humanitarian efforts. For example, the history of family planning in Bangladesh exemplifies both the challenges and the successes of a concerted national approach. According the Center for Global Development, in the mid-1970s, a Bangladeshi woman had more than six children on average: “In combination with poor nutrition and lack of access to quality health services, this high fertility rate jeopardized the health of both the woman and her children”. The subsequent Bangladesh Family Planning Program saw female outreach workers going door to door to provide information and “stimulate a change in attitudes about family size”. The use of contraceptives among married women increased from 8% in the mid-1970s to 60% in 2004, and fertility decreased from an average of more than six children per woman to slightly more than three — a huge demographic change in just 30 years.

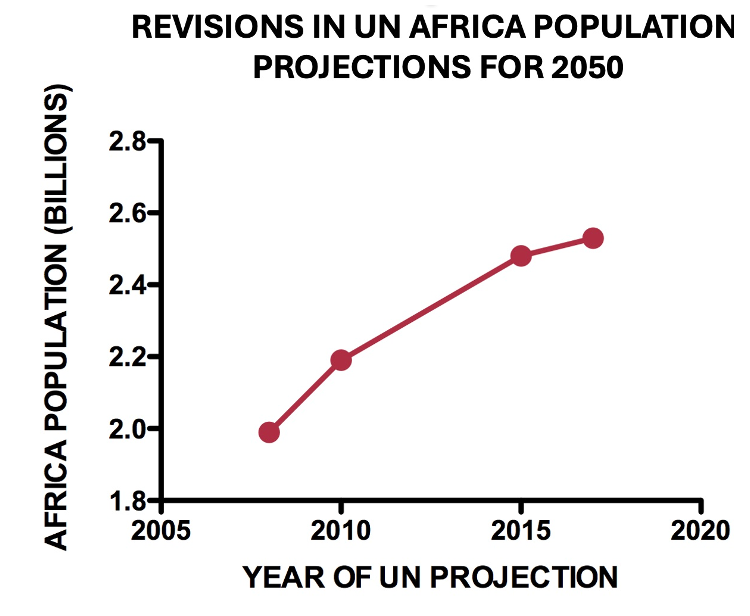

The UN has also consistently underestimated Africa’s population with multiple upward revisions over the last decade or so (Fig.1). Sub-Saharan Africa’s progression to a demographic transition has differed from other less-developed areas, and has proceeded more slowly. Thus the 2021 fertility rates for some African nations, particularly in the Sahel region, are barely different from those in 1950’s.

The preceding discussion clearly demonstrates the uncertainties of population projections and also the possibility of rapid changes in population momentum. Both of these factors have major implications for the environment.

Environmental Impacts

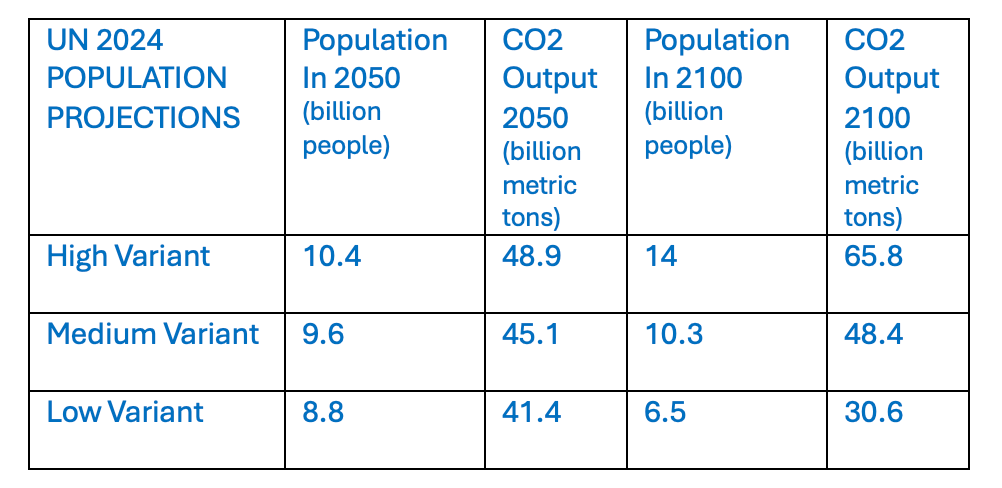

The 2024 UN population projections include three potential scenarios based on variations in fertility. The differences between the median variant and the high and low estimates reflect the seemingly minor change of +/-0.5 children per female, yet this modest alteration has an enormous effect on total global population estimates and consequently on potential environmental impacts. Take for example the production of CO2. Let’s make the admittedly simplistic assumption that each person’s 2050 or 2100 CO2 output would be equal to the current global average of 4.7 metric tons (I have used current levels of CO2 production per person since it is not possible to know what the future levels will be). Then the projected population and CO2 production estimates would be as shown in Table 2.

In 2050 the difference in global CO2 output between the high and low population variants would be about 7.5 billion tons while in 2100 it would be 35.2 billion tons. In comparison total global CO2 output in 2025 was about 38 billion tons. Thus, different rates of population growth can potentially have an immense impact on CO2 production and therefore on the trajectory of climate change. The calculations are meant to be illustrative rather than predictive since we cannot know how per capita CO2 output will change over the next decades. Nonetheless, the basic argument is valid. Furthermore, essentially the same scenario would play out for many other environmental parameters including plastic pollution of the ocean, rainforest loss to slash and burn farming, poaching of wildlife and over-fishing. They are all impacted by the number of human beings on the planet who intentionally or unintentionally do harm to nature.

One could argue that there might be less environmental impact since the parts of the world experiencing rapid population growth are also areas with relatively low current CO2 emissions per capita. Certainly, it is true both currently and historically that wealthier nations are responsible for most CO2 production. However, this argument neglects several important considerations. First, a number of poorer nations are now urbanizing rapidly entailing a marked increase in energy consumption for air conditioning and other purposes. Second, as discussed in more detail below, there is the prospect of substantial migration from less developed to more developed counties that may have a substantial impact on global energy use and CO2 production. Finally, environmental damage is not limited to CO2 output. Several less developed nations are now having significant impacts on global environmental degradation, for example, through loss of tropical forest to slash and burn agriculture in Brazil and Indonesia, through damage to coral reefs in the Philippines and other parts of southeast Asia, and through increasing wildlife poaching in Africa. All of these phenomena are driven by commercial demand and thus are directly related to population size.

The Two Paths of Population Change: Implications for Migration and for the Environment

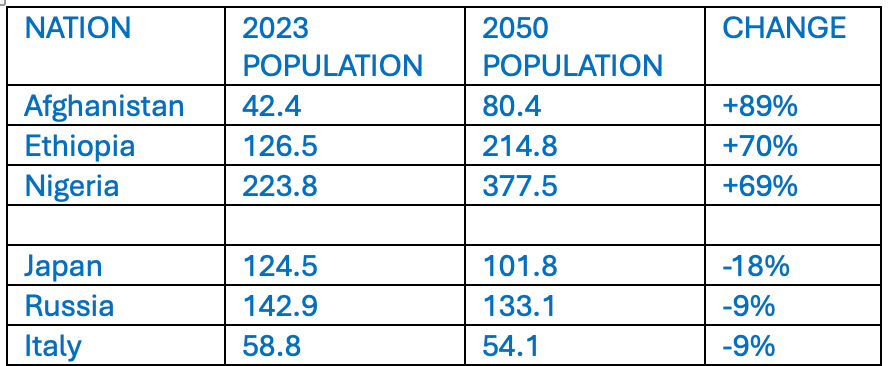

It is important to consider not only overall global population changes but also where these changes are taking place. A number of developed nations, especially in Europe and East Asia, are in the initial phases of unprecedented population declines. In contrast, several poorer nations in Africa and West Asia have populations that are still growing rapidly (Table 3). To some commentators, notably the editors of The Economist magazine, these rapidly growing populations are a blessing in disguise. According to that source, the lagging working age populations of Europe, Japan, China and other slow growing countries should be topped up by energetic youth from Nigeria or Ethiopia or Afghanistan. This of course ignores the social and political backlash that mass migration often triggers in the host country. However, let us pursue this thought and consider the potential environmental impacts of mass migration, using CO2 production as parameter.

Clearly migration from a less developed country to a more developed one will result in a net increase in CO2 as the migrants adapt to the life style of their new home. For example, individuals in France produce 4.133 metric tons of CO2 per year while individuals in Senegal produce 0.411 metric tons, a number typical of many African countries. Thus, one person migrating from Senegal to France entails an increase in CO2 output of about 3.7 tons. The approximately 4 million African migrants in France contribute about 14.8 million tons of CO2, a small but significant fraction (~5%) of the 283 million tons total emissions for the country. Obviously similar calculations could be done for immigration from any other low emission country to a higher emission one. Right now, the total impact of such migration on CO2 production is likely small. But what if the number of low to high emissions migrants increased by 2X, 5X, 10X as nations with declining populations struggled to maintain their workforces to meet policies of economic growth? Clearly that would have a major impact on global CO2 output.

Taking another example, the United States has historically been a magnet for immigrants from across the globe. But what are the environmental consequences if that pattern changes? The Census Bureau has projected the 2050 population of the United States based on several different assumptions about immigration. The mid-range projection is 388 million, with high, low and zero immigration projections at 420, 376 and 326 million ( Fig.2).

The difference between the highest and lowest projections, about 91 million people, would surely have a major impact on national CO2 emissions as well as on many other environmental parameters. Assuming that each person’s 2050 CO2 output would be equal to the 2022 USA average of 14.2 metric tons, then 91 million additional people would add 1.3 billion tons of CO2 to the national output. By comparison total USA CO2 output in 2022 was about 4.9 billion tons. Thus, changes in migration patterns can have dramatic impacts on national levels of CO2 production. Further, assuming that the immigrants come from areas with low per capita CO2 output, then mass migration to the USA would also result in a substantial increase in global CO2 output.

But how do these Census Bureau projections stack up with the recent history of immigration to the USA — are such enormous differences in immigration-based population projections reasonable? The mid-range Census Bureau projection is based on a net migration of about 1 million people per year while the high estimate is based on about 1.7 million per year. Online data on net immigration over the years seems to be somewhat imprecise with different estimates provided by different sources. Thus, Macrotrends indicates that annual net migration over the last two decades increased from about 1.3 million in 2004 to 1.9 million in 2016, but back to 1.3 million in 2023. By contrast, figures from the Congressional Budget Office agrees on 1.3 million in 2004 but stipulates 2.7 million in 2022 and 3.3 million in 2023. If these very high levels of immigration were to continue, the 2050 population of the USA would be far beyond the Census current high estimate and correspondingly CO2 emissions would be enormously increased.

However, events can quickly go in the opposite direction. The Covid pandemic resulted in a rapid drop in immigration to about 0.3 million in 2020 and more recently the current administration’s extremely harsh treatment of immigrants has done the same, with ‘border encounters’ declining from about 190 thousand in February 2024 to about 11 thousand in February 2025, with low levels continuing through the year. If this pattern of almost zero migration persists, the USA will be on track for a population future very different than that envisioned by the Census Bureau mid-range scenario and consequently for a vastly lower CO2 output.

Rather it simply points out that immigration patterns can change very rapidly in response to a variety of factors and that such changes can have substantial effects on population size and thus on CO2 output that play out over the course of only a couple of decades. Once again, this analysis negates the idea that population changes take place too slowly to play a major role in affecting climate change.

Environmentalists have often been strangely reluctant to push population control as a way of mitigating climate change and other harms to the natural world. Perhaps asking people to change their reproductive habits conflicts with current notions of political correctness. Such cultural delicacy seems bizarrely misplaced, however, as both rich and poor nations careen toward environmental Armageddon. It is quite clear that population reduction could be a major tool for blunting CO2 production as well as a plethora of other environmental impacts, but it is barely mentioned in discourse about climate change. In my view, that needs to change!

Total fertility in some countries remains very far above replacement level. A concerted effort is needed to change the social and economic conditions in those countries that lead to high fertility. Helping people out of poverty coupled with strong family planning programs can rapidly alter population trajectories even in countries where religious and social factors work in the opposite direction. Wealthy countries should be foresighted enough to see that aid to poor countries experiencing rapid population growth not only benefits the people there, but also reduces global environmental stress. Unfortunately, events are moving in the opposite direction with several wealthy countries, particularly the USA, dramatically reducing their humanitarian assistance programs.

People concerned about our current environmental catastrophe should of course promote the adoption of solar energy and other environmentally friendly technologies. They should of course continue to promote lifestyle changes that are good for the environment. However, they should also welcome the fertility declines that have taken place in many developed nations and not be swayed by the pro-natalist nonsense that has been adopted by some right-wing groups. Most of all they should advocate for a resumption and major expansion of aid to less developed nations, aid that includes significant funds for family planning. A relatively inexpensive investment in fertility management may well turn out to have a greater positive impact on the environment than massively expensive tech-fix solutions.

Epitteto is a biomedical scientist with a lengthy academic career now interested in the complex connections between the environment, population and technology.

Leave a comment