I’ve lived a long time and that gives me some perspective on what has happened to my country over the years. To my mind one of the most depressing trends in the United States has been the erosion of the middle class and the growth of extreme economic inequality, with a small cohort of people monopolizing most of the wealth. Some economists, notably Thomas Piketty, have postulated that increasing inequality is an inevitable feature of our capitalist system and have traced its evolution over more than a century. However, looking further back in history one can find an exception to this trend.

In the 14th century the bubonic plague swept over Europe causing catastrophic illness and death, leading to a drastic decline in population. A surprising result of that decline was a long-lasting betterment of economic conditions for many agricultural and industrial workers. Another corollary of plague-induced depopulation was a remarkable change in environmental conditions, with a major expansion of forested areas in western Europe. Thus, one might ask if there are economic and environmental lessons to be learned from the time of the Black Death in the context of current trends toward reduced populations in many developed nations.

Population Decline and Pronatalist Anxiety

In many countries fertility rates have dropped below replacement levels indicating that populations will decline over the next decades. This has triggered cries of alarm about economic and social collapse, leading to the growth of an increasingly strident pronatalist movement that seeks to induce or compel women to have more babies . While it is hard to parse out the various motivations involved in pronatalism, certainly they include the desire to have ever-expanding markets for the global capitalist economy. Constant growth is the keystone of capitalism and the vast population expansion that took place over the last 150 years strongly contributed to growth, but now that is changing. Will economic growth continue in the era of declining populations? That remains to be seen.

Population Trends and Inequality

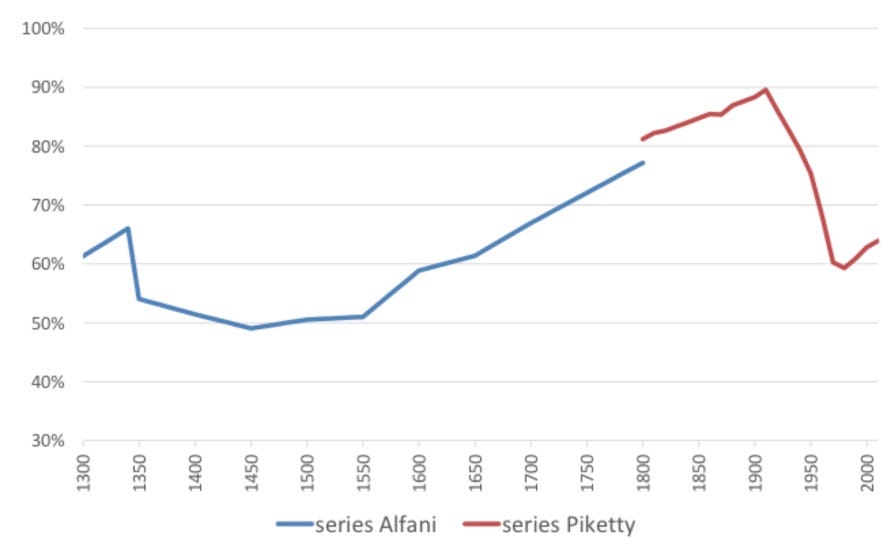

Before discussing the social and economic impact of the Black Death, let’s examine another seemingly inexorable trend in human history, namely rising economic inequality. In his widely-read book Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Thomas Piketty provides a massive amount of evidence documenting that the return on capital consistently exceeds the rate of economic growth. This inevitably leads to inequalities between those who own the sources of production, be it land, factories, or computer servers, and those who provide labor. In Piketty’s review of economic conditions in several developed countries over the last two centuries, the only time that the relative wealth of capital declined was during the period of the two world wars when government intervention drastically altered economic relationships. This is dramatically illustrated in Fig 10.6 of Piketty’s book that shows the share of wealth owned by the top 1% or top 10% of the population in the USA and Europe has been inexorably trending upward for 200 years, barring the wartime interruption.

Recently, however, economists have sought to extend the Piketty type analysis back in time. One study by Guido Alfani examined wealth inequality in several Italian states between 1300 and 1800. As seen in Fig. 1, the share of wealth of the richest 10% moves ever upward, except for a period just after 1300. That period coincides with the zenith of the Black Death in Italy. This analysis reinforces other studies of this period in history.

Fig 1. The share of wealth of the richest 10% in Europe 1300-2010. Alfani 2017

Lessons From the Black Death

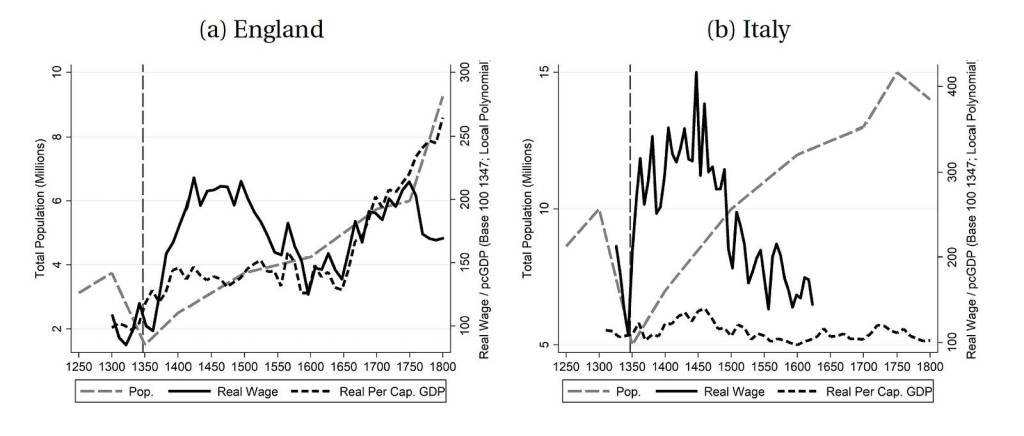

What then was the basis of the change in wealth distribution provoked by the Black Death? Simply put, the sudden shortage of labor raised wages and reduced the return on capital, thus diminishing inequality. The Black Death coincided with Europe’s gradual transition from a feudal to a more mercantile economy and in that context the rapid reduction in the availability of agricultural workers meant that landowners needed to pay them more, while the relative value of their lands decreased. However, when examined in more detail, the economic effects of the plague varied widely from place to place. Thus, as seen in Fig.2, while Italy and England suffered fairly similar proportional population declines, the positive effects on wages in Italy were higher than in England, while the resumption of GDP growth was much slower. Thus, both the underlying state of the local economy and the political context modulated the economic effects of the Black Death. A particularly notable deviation from the trend toward decreased inequality took place in eastern Europe where harsh regimes forced agricultural workers into a more severe form of serfdom. Despite the local variation, however, in general, the decades after the zenith of the plague saw a substantial and enduring improvement in the economic well-being of the laboring classes.

Fig. 2. Taken from this source.

So, can we project that pandemics or other disasters that reduce population will always provide economic benefits to those of the working class that survive? Perhaps not. Later epidemics, including additional outbreaks of bubonic plague, seemed to have more variable effects on European economies, while in our own time the Covid pandemic certainly did little to better the status of workers.

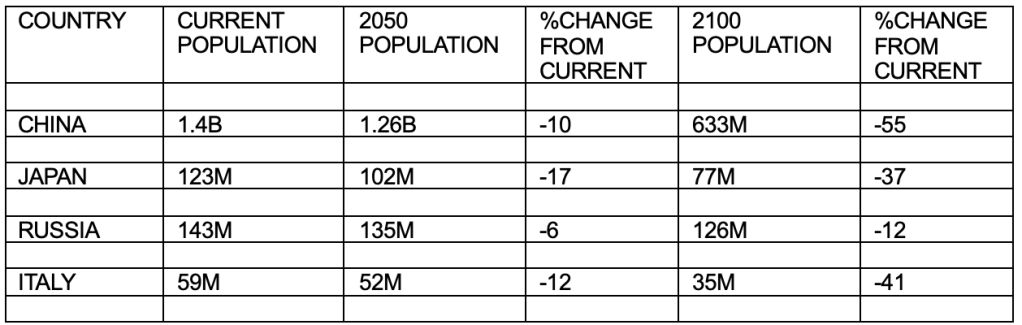

However, the decimation caused by the Black Death was truly exceptional, proportionally far greater than losses in the two world wars or the 1918 flu pandemic. Will the modern world ever see a similar loss of population? The answer, of course, is yes! If UN demographers are correct, between now and 2100 a number of nations will be impacted by population declines comparable to those seen during the Black Death, with some experiencing very substantial declines by 2050. Examples are shown in Table 1 with China experiencing the greatest decline both numerically and in percentage terms.

Table 1. Source UN Population Prospects 2024.

However, in comparing these projections to the losses incurred during the Black Death there are some cautionary considerations. First, long term population projections are often not very reliable, at least in precise detail. Second, the expected population reductions will take place over a time frame of several decades whereas the 14th century plague spread across all of Europe in about five years. Thus, today’s nations will have substantially more time to adapt to anticipated population changes. Nonetheless, for the first time since the 14th century, many nations will experience drastic population declines.

Will Future Population Declines Benefit Workers?

The key question then, is whether such dramatic depopulation will benefit workers and change the distribution of wealth between labor and capital? Will the 21st century repeat the patterns of the 14th and reverse or blunt the rising economic inequality of the last 200 years? As always, long term prognostications are tricky and, as well, there are now forces in play that didn’t exist a few hundred years ago. According to basic economic principles, a shortage of labor will inevitably cause wages to rise. Reduced demand will also reduce the value of capital assets (factories, farmland etc.) and in that way tend to reduce inequality. Thus, if we limit ourselves to ‘classic’ economic considerations, the overall picture suggests that radical population declines will be of benefit to labor and will reduce economic inequality. However, we need to anticipate the impact of additional factors that lie beyond simple economics and for which there were no precedents in earlier eras.

Will Immigration Play a Role?

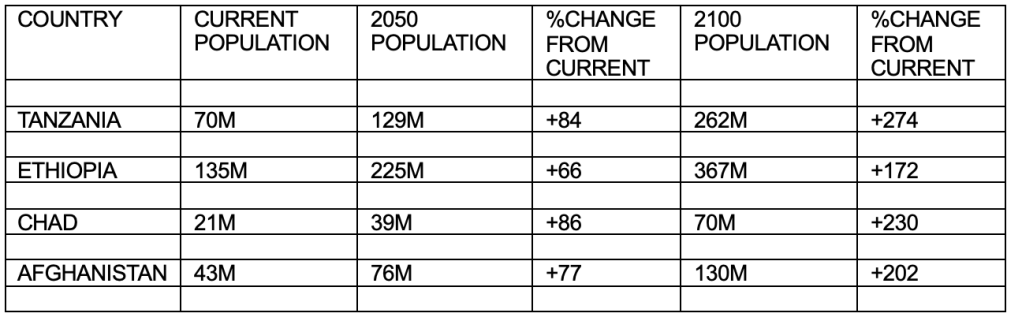

The Black Death reduced populations everywhere it touched. However, current global population trends are quite divergent, with one group of nations facing rapid population decline while another will experience enormous growth. It is among the poorest nations of the world that populations continue to rise rapidly (Table 2). This makes it difficult for those nations to provide adequate educational, health and social services and even more difficult to provide employment for an ever-increasing cohort of young adults. The plight of these nations is compounded by climate change that brings droughts, floods and extreme heat to people who cannot afford to mitigate those problems.

Table 2. Source UN World Population Prospects 2024

One possible consequence of this situation is a massive migration from poorer to richer nations driven by poverty and lack of opportunity as well as by a changing climate. From a purely economic viewpoint it would benefit countries with declining populations to supplement their pools of working age individuals with immigrants from poorer nations. However, it is clear that immigration is as much or more a political issue as an economic one. Surges in immigration to the USA and western Europe over the last few years have created a tsunami of outrage from the extreme right. That the politics of immigration can outweigh economic forces is clearly illustrated by the very recent sharp declines in immigration to Europe and particularly to the USA . Thus, it is unclear whether the imbalance in population trajectories will have much of a long-term effect on the economies of those nations undergoing population decline.

The AI Factor

A wild card in these considerations is the role of artificial intelligence and automation. AI has been evolving at an accelerating rate with enormous implications for the economy and society. Some experts have predicted that AI will decimate jobs in service industries and in middle management, as automation has done in factory work. Others see AI as a partner that will enhance but not replace the role of people in many types of work. Finally, some commentators see AI as having relatively modest economic effects at least in the near future. We are only at the beginning of understanding the impact of AI on the economy and, in particular, the potential interplay between AI and a declining workforce. Will a reduced working age population powered by AI tools lead to vastly increased productivity and parallel increases in worker incomes, or will there simply be an erosion of the value human labor? One potential concern is that the most powerful AI tools will be controlled by a handful of ultra-rich corporations. This notion is based on the ‘scaling hypothesis’, namely that the major way to increase AI performance is simply to have AI systems get bigger and bigger, a very costly process that only the richest corporations can afford. If that were the case, the spread of AI would accelerate economic inequality despite any effects of a shortage of human labor.

Impact of the Black Death on the Environment.

The 14th century pandemic resulted in a drastic reduction of rural populations with cultivated fields and even entire villages being abandoned. Both direct mortality and the migration of rural workers to now emptied cities played a role in the decline. In unused fields first shrubs then trees took hold, resulting in a fairly rapid and rather extensive reforestation in many parts of western Europe. Paleoecology studies of pollen grains demonstrate an extensive switch from cereals to forest species such as oaks. Additionally, there was a significant reduction in CO2 levels during the period that overlapped the Black Death; however, a cause-and-effect link has not been firmly established.

While our era has mainly been preoccupied with deforestation, there have been some notable examples of the reverse. Thus, there has been extensive re-growth of New England forests over the last century due more to rural to urban migration than actual depopulation. A more recent example concerns Japan where the emerging 21st century population decline is most advanced. As the Japanese rural populations wither, substantial reforestation and re-wilding has taken place. Thus, recent experience is consistent with that of the 14th century, in that population decline inevitably leads to a rebound of the natural environment.

Summing it Up.

One of the few times in history when inequality between capital and labor diminished was during the massive depopulation caused by the Black Death. This raises the possibility that the anticipated future population declines in many countries will be of benefit to workers. However, the multiple differences between the 21st and 14th centuries makes evaluating this possibility very challenging. In simple Economics 101 terms, a reduced labor supply should increase wages and lessen inequality. However, we seem to be on threshold of revolutionary changes in computing capabilities and automation that may diminish the need for human labor in many fields. The resolution of these complexities will likely come, not through simple market economics, but rather through politics. It will be essential for governments to find a way to harmonize advances in technology with basic human needs, not only for income, but also for the opportunity to contribute to society through meaningful work.

A clearer picture emerges regarding the environment. Whether in the 14th century or the 21st century, a reduced population leads to a rebound of nature. Trees grow and animals roam where fields and houses once stood. Thus, while the coming convergence of AI and population decline will no doubt lead to economic challenges, it may also give the natural world a chance to recover from the many depredations that mankind has imposed on it over the last two hundred years.

Leave a comment